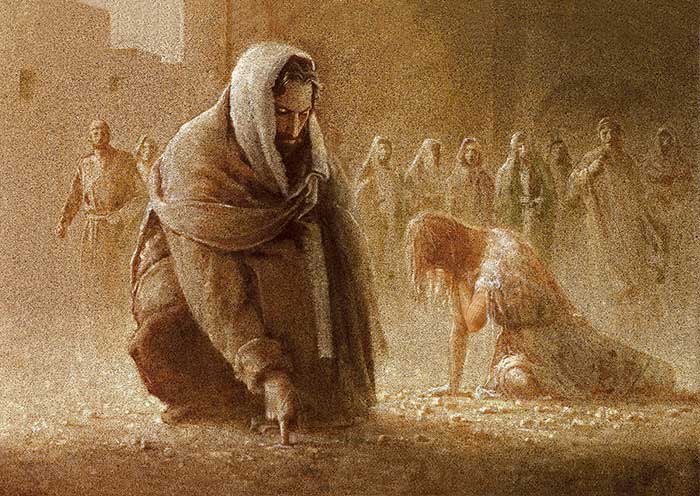

The Woman Taken In Adultery

The bible (John 8:3-8:11) tells us the following story:

And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst, They say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act.

Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou? This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not. So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her. And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground. And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst. When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee? She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more.

As in other biblical paintings, Rembrandt’s interpretation takes the already amazing teaching story into an even higher level.

He gives human dimension and depth to each one of the characters involved, and adds several figures that are not mentioned in the original story. He is able to convey his subtle observations and insights and teach us a lesson that is applicable to each one of us: living in very different times and culture.

The structure of the painting is reminiscent of some works on the subject of “the day-of-judgment”.

The canvas is divided into 3 levels. The biblical scene occurs on the lower level, while the top level is dark and almost empty. The middle level shows the crowd coming to see the high priest in the temple, completely unaware of the miracle occurring outside.

What were Rembrandt’s thoughts during his work on this painting? Apparently, he painted it during a difficult period of his life. His life with his mistress Hendrikje was condemned by society. And she was not given any legal or economical rights. The art historians believe this painting echo this personal situation.

It raises questions about sin, judgment and forgiveness. What these concepts mean? How are they related to each other? How are they relevant for each one of us, here and now?

To make a work of art relevant for myself, I find it useful to study the background, sources, style and the artist’s life. Then an essential “leap of faith” is required. It is the assumption that in essence, the artist, although living in a different culture and in different times, had a similar inner life to mine, so I can share his experience.

From this point of view, I try to find every character in the picture inside my own inner world. Looked at from the other side: see myself in each one of these characters.

The two Pharisees, dressed in rich clothes, clearly belong to the ruling class. This scene is threatening the social order, thus their own status and riches. They represent the influence of daily life: money, corporations, politics, etc…

They do not care for the woman, nor for her “sin”, or for the law. However, this event has implication to their status and economical position.

The Rabbi, dressed in black is concerned about the law and the place of religion in society. In some way he represents spirituality, religion and philosophy. The meaning of his life comes from following the commandments of Moses and in this case the laws are pretty explicit: the woman sinned, she should be stoned. The fact that the law was given 13 or 14 hundred years prior to their time is irrelevant to him. He is not necessarily inhuman, or merciless, but law is law and has to be followed and protected. If one compromises one law the whole structure might collapse.

It is interesting to note in comparison the other religious figure in the back, near the Pharisees. He is possibly also a Rabbi, dressed in lighter colors, holding a finger to his mouth, considering the unresolved contradictions brought up here. He might have been sensitive enough to consider what goes on in the woman’s heart. For some reason he bring to my mind the name of Joseph of Aramthia, a follower of Jesus who was a Rabbi, a scholar and belonged to the ruling class.

Next to the black Rabbi is a friend or assistant. He puts his hand on the Rabbi’s shoulder, trying to pull him away from the debate. Jesus’ solution might actually be good from political viewpoint. These are turbulent times. Stoning a woman will inevitably attract a lot of attention from the Romans. And maybe it is better to spare her. What is there to gain from this killing?

In fact, next to him stands a Roman soldier. He is far away from home, cannot relate to such extreme religious debate of these strange Jews. Adultery is an everyday matter back in Rome. No one makes too much fuss over it.

Hopefully they will go without stoning; there is enough trouble with the zealous rebels. And the women look too beautiful to waste.

And Peter? He is taking in all the contradictions. He knows the law and respects the reasons for following it. He is a religious man. He is also a devoted disciple, admiring his teacher and committed to him above anything else. He is aware of the weight of the women’s sin, of its social and moral implications. He is also aware of her human nature and suffering. He is a spiritual aspirant “working on himself”, and used to “living the question” and to experience contradictions. Yet, it is painful for him as it always is.

The hand position of the different figures creates a specific flow and rhythm, both visually and emotionally. From the woman’s face to Jesus’ heart and to Peter’s heart and mind.

The Rabbi’s hand is tensed, somewhat aggressive, and pointing down to the woman. Jesus’ hand is on his heart, pointing in the opposite direction from the Rabbi’s. Peter’s hand has a similar posture to Jesus’, but tighter. His hand is not free, it hangs on his robe. He also holds and leans on his stick, echoing the soldier who also leans on a stick. His confusion is visible.

The adulteress woman is dressed in a pure white satin, and bathes in a pool of light. Maybe that is how Jesus is able to see a sinner. See the highest possibilities, the spark of god in every human being, rather than his or her faults.

Jesus’ figure is much taller than all the others. His light and simple clothes contrast with the heavy dress of the Pharisees (ego). One can almost see his body through the garments. Although very involved emotionally, his peace is undisturbed by the very dramatic scene, and by the test he himself is put to.

I could not find a print or even a post card of this work. Nothing in the various art books sold in the National Gallery.

The librarians in the study room said that the extreme contrast of light makes it hard to reproduce, as do the non-standard proportions. The art researchers point out some flaws in the composition. Some critics suggest the painting is unfinished. Others say that the fine details are not in line with the period of Rembrandt’s works, for example, in comparison to another biblical painting of a year later (the birth of Christ). Kenneth Clark mentions the painting and praises it. He comments that Rembrandt worked on it for a long time but does not go into the moral or philosophical issues. He does comment elsewhere in the book about Rembrandt’s preoccupation with forgiveness and compassion.

Some biblical researchers argue about the authenticity of the text. Is all of it from the same period and source? Or the idea of the Pharisees seeking to blame Christ is a later political addition.

For us as students of human psychology, there are more practical points to consider:

Jesus tells the woman: “go, and sin no more”

What is her sin? Is it the act of adultery itself?

Is it being disloyal and going against her marriage contract?

How come Jesus that teaches so strongly against divorce is lenient with adultery?

How do we in the 21st century use this lesson for ourselves?

Do I sin? Do I commit adultery? Can adultery happen without awareness, just by having divided loyalties, or must it be intentional and thus criminal? How do I react when faced with crime, or with breaking the laws? How do I feel about rules that are not being followed?

Jesus’ work is most advanced. He stands up against the common morality, armed only with love and compassion.

He faces the power of money and politics, instinctive fear and emotional temptation and keeps his inner work. This is inspiring.

The crying woman represents an essential part in our work. She must be very aware of death and of her nothingness.

It takes courage to face this reality and cry. The ability to change one’s attitude is built on the courage to see our nothingness, not repress or dissociate and turn our heart to god, even if we cannot see or be in contact with god.

Peter seems to be the only one who is looking at the woman. He is letting in the pain and the fate of another human being, willing to experience it himself. This is compassion.

On our level, we might learn more from Peter and “Joseph of Aramathia”. Although coming from opposite places in life and society, they both give up their “knowing” and stable world-image for questioning and confusion. They are “plunging into the unknown, knowing it is the only way home”. They are trying to change a basic attitude or at least bring inquiry into it. This is something we can all strive to do in our daily life. When faced with a question, with injustice, cruelty or ignorance, we can choose “not knowing” until conscience emerges to give us direction or a different level of “knowing”.