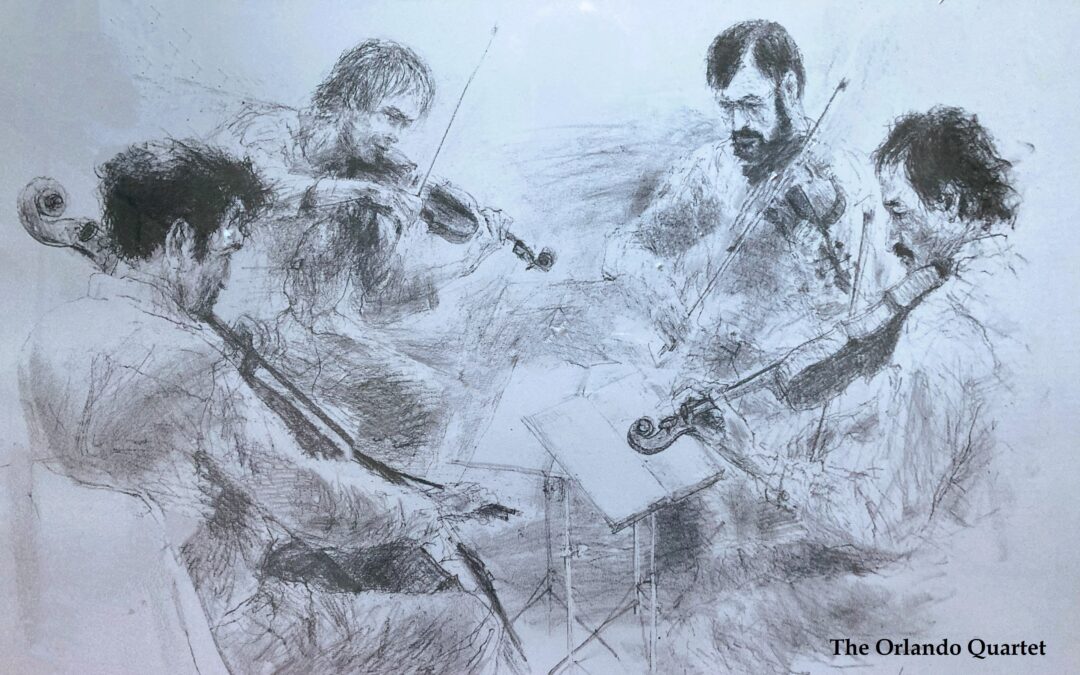

Lessons from Beethoven’s Late String Quartets

Andante from quartet 131

The composer Ludwig Van Beethoven wrote 17 string quartets during his life. Six of them in a span of two years, 1825-26, just before his death in March 1827. These quartets were the only large-scale compositions he worked on, after the completion and performance of his ninth symphony in 1824.

After a life of loss and pain and very little joy, Beethoven died at age 56, completely deaf and deprived of his greatest pleasure of hearing music. He was struggling with anger, fear, and sadness, in addition to physical illnesses; and searching for a meaning that could bring deeper acceptance.

These late quartets are a testimony of his human struggles. Listening to them I find myself deeply experiencing my own human struggles, caught in confusion between impossible polarities. The quartets provide a roadmap for anyone trying to make sense of the inner world of strong emotions that often correspond with challenging external life events.

The opus numbers of the late quartets in the order they were written are: 127, 132, 130, 133, 131 and 135. I will refer to them hereafter just by these numbers. Online performances can easily be found by looking for “Beethoven quartet ###”

Basic Emotions

When I teach clients the basics of emotional vocabulary, aiming for greater affective awareness, I usually start with “Mad, Glad, Sad, Scared, (or afraid).” The rhyming names help to remember a starting point for mapping the emotional landscape and making sense of it. Naturally, once one can name these four categories of emotions, it is possible to look for finer subtleties and details; Sadness, depression, hopelessness or just feeling blue?

The animated film Inside Out shows the inner world of a girl who is moving to another state as comprised of five characters representing basic emotions. In addition to “Mad, Glad, Sad, Scared,” a fifth character, representing disgust, is added to the collection. That film was made with close guidance from brain and psychology experts. Some discussion went into the decision to exclude guilt, shame, and curiosity from the group of emotions represented.

Assuming that all emotions are useful evolutionarily, it makes sense to inquire what purpose each one of them serve.

Glad or “Joy” as called in the film, is the only ‘good’ feeling, arising from a fulfilled need, as explained later. Joy is related to the essential life force. Mad or anger, and disgust are empowering emotions that bring agency. They prompt actions that physically remove the individual from danger or take steps to protect from or confront danger.

Fear can be an earlier impetus towards action and can also lead to inaction or freeze.

Sadness can be a step towards acceptance of loss and finding a new equilibrium and possible new meaning that feeds the life force.

One of the turning points in the film is when Joy and Sadness recognize their mutual value and learn to accept each other and work together.

My goal here is exploration, inspired by Beethoven’s timeless music, towards better understanding of some of the most fundamental emotions, each of us has. How they direct and control our lives and how they can be managed to some extent, or at least understood on a deeper level. If we are lucky these emotions can be transformed.

Our culture looks down on emotions as a disturbance to be removed or suppressed. Significant parts of the population are using anti-depressants or anti-anxiety drugs that dampen emotions. People in grief are often told after a short time to “get over it.”

I see the Beethoven late quartets as a brave attempt to be with difficult emotions, experience them fully to the point where they became intelligent and allies of life that is freer and fuller.

How can I tell what Beethoven was feeling?

I cannot. These quartets were written two hundred years ago in Vienna, and even in mid-20th century, many considered them avant-garde. Certainly, they were well ahead of their time when written and many of the music loving audience at the time, considered them incomprehensible or offensive. On the other hand, Franz Schubert, who asked to hear 131 on his death bed, less than two years after it was written, said “after this, what else is there to write?!”

Observing art, we cannot tell for certain what the artist felt, we cannot even tell for certain what a person next to us is feeling. And yet, as mammals, we can sense the emotions of other mammals. The technical mechanism is mirror-neurons. These are parts in our brain that translate an observed behavior of another mammal (seen, heard, or sensed), into our own feeling. Another brain circuitry allows us to distinguish these mirrored emotions from those generated by our own body. In this way, dogs and horses can be fairly tuned into human emotions and respond empathically to them.

The case here is more complex: I am not in the presence of Ludwig. Instead, I have only the amazing creation of his mind as interpreted by other musicians. I can also refer to fragments of biographical data that lead to mental speculations about his state of mind.

For these reasons, professional musicologists are careful not to make any definitive statements about the emotional or intellectual messages, communicated in a piece of music, or in any art for that matter.

With this disclaimer of complete subjectivity, I take the liberty to share my own feeling and thoughts evoked by listening to the quartets. I hope and trust that you, the reader, use your mirror neurons in a similar fashion. Maybe my reflections can serve as trail-heads for your own inner explorations, knowing we both are mammals.

Non-Violent Communication

Marshal Rosenberg, the creator of Non-Violent Communication (NVC), claims that all our emotions are like indicators on a car dashboard, telling us about needs that are met or unmet.

What unmet needs are behind anger, fear, and sadness, and behind the various shades of each of these emotions?

When these unmet needs are partially or fully met, what emotions arise?

‘Joy’ might refer to the emotion that arises when sadness is resolved. When the unmet needs that led to fear are resolved or met, it might also be called ‘Joy.’ Similarly, when anger is resolved we might also feel ‘Joy.’ Are there some subtle or not so subtle distinctions between these types of joy? Are there more distinctive names for them?

Here are some possible suggestions to consider from the NVC feeling inventory:

Peaceful, calm, trusting, confident, safe, grateful, touched, open hearted, pleased, relaxed, …

Both NVC and the film Inside Out teach the value of emotions as indicators. Without that understanding, many people try to eliminate negative emotions, as they are usually unpleasant or even unbearable. People often try chemical or behavioral means to eliminate the difficult emotion. Sometime that leads to addiction. Other people follow a religious or spiritual path that claims to teach how to eliminate negative emotions; Frequently glorifying repression or suppression as a virtue.

NVC and Inside Out point towards inquiry and acceptance. Beethoven’s music points in that same direction. That can be seen in a few written biographical records, and more clearly by following the emotions that arise as one listens. Acceptance is different from resignation, just like openness and joy are different from closed and bitter. That distinction is one of the lessons from the quartets.

Other religious or spiritual teachings point similarly toward acceptance and transformation through deep inquiry. Using the difficult emotion itself as a reminder and a focal point for soulful work.

Tonglen

Tonglen is an ancient Buddhist practice, documented as early as the 11th century.

Tong means ‘Giving’, Len means ‘Receiving.’

The practice consists of alternating emotional focus, synchronized with the breath. With the in breath, one takes in the suffering, on the out breath one sends hope, courage or well wishes. The subject of the emotional focus can be an individual, a group or oneself.

The practice can last just a few breaths or extend to many minutes or even hours. It is both a meditation and a prayer.

Starting with an intentional taking in of pain and suffering is radically different from any approach that tries to get rid of painful feelings or in any way ignore them. It is an acknowledgment of being part of a world that inherently includes suffering. Breathing out hope and good wishes, is a statement of agency. The trust in the possibility to positively affect or influence the lives of others.

The frequent alteration synchronized with the rhythm of the breath, provide a delicate balance. It helps to feel deeper, and to our limit, without being overwhelmed. As is well known in the studies of performance, be it athletics or music; practicing at the limit develops the muscles and slowly extend our capacity.

The emotions that are being explored in the late quartets are overwhelming. Such emotions can lead to stuckness: feeling trapped in a negative feeling with no way out. The emotional experience can turn into a feedback loop where the emotion triggers thoughts that further trigger the emotion. Anger leads to muscle tension and then leads to thoughts of revenge or resistance that cause more anger that in turn brings even more difficult thoughts and more muscle tension. This kind of a cycle ends only with explosion or exhaustion; The energy breaks the container in some sort of acting-out behavior, or alternatively, the energetic fuel is slowly depleted, resulting in some form of depression.

Practicing Tonglen enables one to stay in between exhaustion and explosion, not knowing, not resolving yet feeling more deeply and looking for information and meaning in the difficult emotion itself.

There is no indication that Beethoven was aware of this practice. Yet, he uses several techniques to alternate emotions and gradually increase the intensity. He sometimes interrupts an idea that is already familiar, leaving the listener questioning or lost. He also uses polyphony, or playing different melodies at the same time, often bringing different or contradicting emotions at the same time.

More specifically, he often uses fugue like writing, where the same musical idea is presented at different times, changed, expended, reduced, or modified in some other way, and usually against (counterpoint) another musical idea. This style of writing can be used to explore an emotion more deeply and from different directions, and it can also be used for Tong Len, alternating continuously between different emotions.

Style and Form

In a very schematic way one can count three or four different general forms of movements in the late quartets.

- Movements based on structure, conceived by the mind. Often written in the form of a fugue. For example, the first movement of 131. At other times they follow a stricter sonata form. In all these cases, the form and the thought are what holds the musical material together. The challenge is to find emotional expression through the structure.

- Dance-like movements, coming from the body. For example, the second movement of 131. These movements are often fast and energetic. The repeating dance rhythm keeps the musical material together. The challenges are both to express a lasting idea and a deep feeling through the dance movement, dominated by the rhythm.

- Lyrical movements, originating from an emotion. For example, the sixth movement of 131, or the Cavatina (fifth movement) of 130, where scholars believe they have found a tear drop on Beethoven’s original manuscript. These type of movements express pure emotions, often sadness, sometime hope, and sometime search for safety, especially when sounding like a lullaby.

- The fourth “style” refers to movements that primarily tell a story. The third movement of 131 is a short recitative, announcing the very long slow movement that is the heart of that quartet and almost a third of its length. The first and last movements of 135 are “program music” using a leitmotiv: “Must it be?” “Yes, it must be!”

Most of the time, these general categorizations are mixed and deviated from. Beethoven explores form becoming lyrical, dances becoming an idea and emotions turning into a dance, especially when he believes that he approaches acceptance.

Listening with the awareness of the form, I can feel dissonances in my own emotions. Something wants to relax into safety with lyrical movements, yet existential questions or unhealed pain is gnawing and would not get comforted. Energetic dances can stimulate both joy and anger and it can be uncomfortable to hold both.

Acceptance

It seems to me that acceptance is the main thing Beethoven was looking for in the whole project of the late quartets. He knew that his days are numbered and he asked the difficult questions: “Is there a meaning?” “Must it be?” He appreciated his life work; he probably knew that he moved the whole musical world into a new direction; namely, the romantic era. Yet he was miserable; his personal life was worse than ever; the last human relationship with his nephew was broken and above all, he was tortured by his deafness. At the same time, he was greatly admired by the Viennese concert goers, most of whom he detested as idiots that do not understand his music.

The question and answer “Must it be? Yes! it must be!” were written into the score of 135. Yet, some scholars say it was a joke, the story is that one patron missed one of Beethoven’s late concerts and Beethoven wrote to him that he must still pay the concert fee. The patron asked “must it be?” and Beethoven answered “Yes! It must be!”

Regardless if that incident was a joke reference or a deep philosophical inquiry, there is plenty of evident throughout the quartets of asking deep existential questions, often in a structural movement. The structure, or the lyrical theme, or the dance breaks down at some point and the listener remains puzzled, “Where are we going?” A good example can be found in the main angry theme of 133. Beethoven is shouting at God “this is not fair” and then the fugue develops into impossible density where all sense of order and meaning is lost.

The last movement of 131 slowly combines structure, dance, and lyricism into a unified whole. I hear it as accepting anger, sadness and fear and ending with a deep, yet grave joy.

On the other hand, the fifth movement of 131, starts with a very confident dance, turns it into a joyous expression, and celebrates his finding. One can hear him say in the background “I got it! I got it!” Yet, by the end of the movement, the structure crumbles, the deep questions and doubts surface and depression and sadness take over, leading to the sixth movement. One of the most sad and heavy in the whole corpus.

Anger

Anger stands in opposition to perceived reality.

A large sub-type of anger is a response to actual or perceived boundary violation. The individual notices a hole in the fence or an intruder inside what one believed to be their private space. They are not feeling safe.

The sympathetic nervous system is activated, blood and hormones rush to the extremities preparing for self-defense: fight or flight. There is a need to protect the privacy and possibly to defend one’s own safety.

One can argue that fear, or the detection of danger is a precursor to anger, even when they happen in a quick succession. The present anger is directed at an imagined future situation.

There is also anger about the past. In the late quartets I find more of that later type of anger. Beethoven is angry about his loss of hearing, about failing relationships, about endless betrayals and about audience misunderstanding of his music and his greatness. Some optional names for these related feelings: Indignation, outrage, and resentment. An image that keeps coming as I hear some movements in the quartets is shaking a fist against God and against fate. “How could you do it to me!?” yet Beethoven is not religious, and in his youth believed very much in the French revolution and its declared values.

Another image is Zeus thunder bolts, a little over two minutes into the first movement of 130, when the fast wiggly movements come quickly down. Similar feeling comes from some movements that start with a few loud and angry chords.

Fear

Every animal has some mechanism of detecting danger and attempting to avoid it. Without it, the probability of survival is very low.

On the neurological level, fear leads to fight-or-flight response, using the sympathetic nervous system. Both require enlisting of all resources towards the immediate survival requirements.

Anger might be more associated with ‘fight’ response. Yet, ‘flight’ includes similar emotions that can be seen as another shade of anger. These can include hate, wish for revenge, and possibly disgust.

When the individual assesses in the moment that both fight and flight are not an option, the choice is often to ‘freeze’ or collapse. The vagal response reverts to a more primitive mode, and withdraws energy to the core. Emotionally, this can lead to deep sadness.

Fear in quartets usually appears with a complementing comforting theme. A good example is the third movement of 130 where jarring movements alternate with lullaby like themes. 133 also has several places of such alternates.

Sadness

Sadness usually includes or stems from a sense of loss. Loss of a prized object, loss of a beloved friend or relative and loss of a capacity. All these lead to loss of meaning. One’s identity is shattered and one cannot perceive a new identity without the lost object. The process of grief is the gradual repair of identity or rebuilding a new one. An awareness of the loss is a necessary part of successful mourning. Yet, often the loss is below the threshold of conscious awareness, and the dark sadness felt in the body leads to loss of energy, or even to lethargy that makes further awareness more difficult, as the focus is drawn to the pain itself without connection to a cause. All one wants is to remove the pain.

Sadness is expressed in each one of the quartets. Yet, the Cavatina from 130 is a unique example of stating the depth of sadness along with willingness to be at-one with it, and even find its beauty.

Relationship to Authority – Life-force and form

Beethoven grew up in an abusive household, with a father that wanted to mold him into a second Mozart. Unlike Mozart, almost everything Beethoven created is labored and earned with sweat and tears. He was rarely fully pleased with his work. He was always longing for melodies that did not come easily to him. His musical talents made it easy to learn forms such as Sonata or variations. Yet there is often a conflict between his free and rebellious spirit, that identified with the French Revolution and later with Napoleon, and the strict following of forms.

The Dalai-Lama recommends to “Learn the rules very well, so you know how to go around them.”

J.S. Bach’s music is a good example of that approach. His music is always orderly and following the form. He was the greatest Fugue writer ever, and said to be able to improvise a 3-part fugue. Yet, in his music the form always enhances the musical material towards a deeper and fuller emotional expression.

Beethoven on the other hand struggles. In the late quartets this is very apparent, from the 4 notes that start 132 and repeat in several other places, through the fugue in 133 that gets clogged in an unpleasant way.

I resonate with Beethoven’s feeling and conflict. On the one hand I admire the mathematical beauty in form, architecture, and symmetry. Sometime it can bring some sense of safety and even calmness. Yet, most of the time, any sense of rules evokes a need to change or break them. They are experienced as imposing or limiting my life force and its free deep expression.

The end of 133 might be Beethoven’s best attempt to find peace and maybe resolve that question. He becomes free in the form, dances through it, and turns the heavy themes into a lyrical and sweet song.

More on Acceptance

Unlike the other emotions explored here, acceptance requires moving against human nature and even mammalian nature. Anger, sadness, and fear tell us about an unmet need and try to get us to do something that will change the situation. These emotions imply suffering, and the natural move is towards avoidance of suffering. Acceptance on the other hand, looks at suffering directly and tries to make meaning of it rather than avoid it or change it.

Acceptance is NOT resignation; although both include some understanding that the specific cause of suffering is here to stay and beyond our control. Resignation leads to further sadness, lack of liveliness and bitterness, while acceptance “uses the Lemons to make Lemonade.”

A lot of training and practice is required to look at suffering and see it for what it is, without blame or shame. Gratitude is probably an essential element that cannot be presumed, forced, or imitated. One must find a genuine sense of appreciation for what IS. Often that means a wider perspective from which the individual suffering starts to make sense, and some aspects of it can be seen as serving a bigger goal.

The Cavatina of 130 and the slow movement of 135 both explore the acceptance of sadness. Both arrive at a high and ethereal second theme that reminds me of the “New Voice” in Mary Oliver’s poem “The Journey,” quoted below its last part:

…It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voices behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do–

determined to save

the only life you could save.

The message is very clear, Beethoven probably knows that he is on the way out of the world, yet he dares going deeper and deeper into his feeling and after a life of extreme loneliness, finds company and solace there with his own true voice.

Relationship to Beauty

Beethoven declares his gratitude for his healing from illness in an epitaph on the slow (third) movement of 132. The common motive of four notes, often two half note pairs, that is present in many movements throughout the late quartets, is introduced in the first movement of 132 as the main theme. Yet, in this quartet, as in 127, there is still great attention to beauty and appearance. As if Beethoven cares to make sure things look right. Later, in 130 and onward, feeling gradually start to show as they are, including the more raw expression of anger, fear, and sadness. Of course, there are many beautiful moments, and there are many moments that are not pretty. Especially in 133, the dense fugue feels very disturbing.

The Search for Simplicity

Beethoven was a complex person. He was a deep thinker and his music introduced a new level of complexity never seen before. Yet, throughout his life he was searching for simplicity. In the music, the quest for the simple beautiful melody is apparent in many of his compositions. The “Ode to Joy” in the final movement of the ninth symphony is a good example of that search.

It is as if he was saying “What good is all this sophistication and exploration if it leads to further misery and depression?!”

In the quartets, this search for simplicity often comes in a short dance movement. After thanking God for his healing in the third movement of 132, The fourth movement is a short and simple dance. Yet, through the exploration of simplicity the doubts and the questions are always arrived at. As if it is never enough. Towards the end of that movement there is a recitative like section where doubt and fear come in, leading to another simple melody in the last movement. However, resting in that calm and simple tune does not last long, and the sadness takes over again. The questioning, speech like section becomes its own movement in 130 and 131.

William Blake, a contemporary of Beethoven, said:

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy

He who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity’s sunrise

It seems that Beethoven was eager to “bind to himself a joy”

Only at the very end of the cycle, the simplicity is accepted with joy and serenity. The finale of 130, the very last piece Beethoven wrote, replacing the original last movement that became 133, is a wonderful example of simplicity and complexity that complement each other. That different attitude towards simplicity can also be found in several movements of 131.

I would like to believe that Beethoven found at the end an inner place from where he could say with Walt Whitman:

…May but arrive at this beginning of me,

This beginning of me—and yet it is enough, O Soul,

O Soul, we have positively appeared—that is enough.

Listening Meditation and notes

I studied the late quartets in many periods of my life. Occasionally in live concerts. In the process of writing these thoughts, I listened many more times to the whole set. I find it useful to follow the quartets in the order they were written: 127, 132, 130. Great Fugue (133), 131, 135.

If you are not attracted to this music, you might stop here, hopefully learning something from these reflections. That will be akin to looking at a black and white photograph taken in an amazing trip. Thus, I highly recommend that you take the plunge and listen to everything, about 4 hours of some of the greatest music ever, maybe following some of the notes below.

A possible compromise can be to pick just a handful of movements, exploring the transformation of sadness. Starting from the first questioning movement of 132, to third movement, where the answer to the question is presented as gratitude and a touch of self-pity. Then, the fifth movement (Cavatina) of 130, where sadness is felt to its dept, and then, the short sixth movement of 131 where there is full acceptance. Finally, in the third movement of 135, sadness and joy become one, and we can hear the soul singing through both. A hint of this transformation is already in the Cavatina.

127 was written not long before the others. Musically it has many of the elements of the other quartets, thus justified to be called a late quartet. Yet, I can find in it only a slight hint for the emotions and questions explored in this article. It is however a great masterpiece that I love listening to; just not expressing most of what I explored here.

As you listen, I invite you to look first for the basic emotions listed above, asking what need is not met, for you and maybe for Beethoven.

Then try to listen for doubts and questions that might lead to transitions. Joy into fear or anger; Anger or sadness into acceptance or resignation; fear into anger, anger into sadness. Maybe consider other names for these combined emotions.

And in another listening, try practicing Tonglen as you listen. Allow the strong emotion to arise from the music, as you breath in, find your associated memories or thoughts, then try reverse the negative emotion on the out breath and find hope, joy, blessing or well wish for the subject of the feeling; another person or yourself.

In the individual quartet notes below, there are examples of places that demonstrate to my subjective hearing, the emotions and the transitions I described. There are many more, so please take these as subjective suggestions.

Conclusion

The resolution Beethoven drives towards, can be expressed through the Buddhist four noble truths; in a free translation: there is suffering, the causes of it are ignorance and attachments, there is a way out, lets practice that way.

Beethoven can be said to follow the Tao, in showing us a non-dual perspective towards the deep emotions that trouble him. By feeling them fully, and inquire deeply into their sources, they change their nature and become allies to the life force.

Joy and sadness are not opposites but rather complementary; they include and enrich each other. That way sadness brings meaningful gravitas and joy becomes multilayered. Anger and joy are not opposites but complementary; they include and enrich each other. Anger is distilled into pure potential energy and joy grows more vibrant and alive. Fear and Joy are not opposites; they include and support each other. Fear turns into deep observation and knowing without judgment and joy becomes wiser.

Thank you for staying with me for the length of these thoughts.

The following pages are some notes for a guided tour through the quartets, should you want to further explore listening.

I included a link to a favorite recording in each section.

References

- Tong Len

Pema Chödrön gives Tonglen instruction in as follow

“On the in-breath, you breathe in whatever particular area, group of people, country, or even one particular person… maybe it’s not this more global situation, maybe it’s breathing in the physical discomfort and mental anguish of chemotherapy; of all the people who are undergoing chemotherapy. And if you’ve undergone chemotherapy and come out the other side, it’s very real to you. Or maybe it’s the pain of those who have lost loved ones; suddenly, or recently, unexpectedly or over a long period of time, some dying. But the in-breath is… you find some place on the planet in your personal life or something you know about, and you breathe in with the wish that those human beings or those mistreated animals or whoever it is, that they could be free of that suffering, and you breathe in with the longing to remove their suffering.

And then you send out – just relax out… send enough space so that peoples’ hearts and minds feel big enough to live with their discomfort, their fear, their anger, or their despair, or their physical or mental anguish. But you can also breathe out for those who have no food and drink, you can breathe out food and drink. For those who are homeless, you can breathe out/send them shelter. For those who are suffering in any way, you can send out safety, comfort.

So, in the in-breath you breathe in with the wish to take away the suffering, and breathe out with the wish to send comfort and happiness to the same people, animals, nations, or whatever it is you decide.

Do this for an individual, or do this for large areas, and if you do this with more than one subject in mind, that’s fine… breathing in as fully as you can, radiating out as widely as you can.”[6]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwqlurCvXuM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-x95ltQP8qQ

Individual Quartet Notes

127

I mentioned above that 127, although stylistically belongs in the late quartets, does not pose the deep emotional and existential questions I am exploring here. I challenged myself to listen to it again and check that opinion and I invite you to do the same.

It is a great masterpiece beyond doubt, and I had great time listening again. The second slow movement is the model for the rest of the cycle, with a very long, 15-17 minutes exploration that attempts to cover a whole range of emotions. In this quartet the questions are hinted at, yet the form and appearance take over and beauty take priority over truth.

132

This quartet was my favorite for many years. The four-notes theme goes throughout the rest of the quartets in several variations. In the first movement, the four-notes theme is repeated by each instrument in a short sequence creating a wealth of new harmonies. Here is also a demonstration of the immense creativity and inventiveness of Beethoven, creating a whole world from four-notes. The existential questions are no longer hidden.

Note in the second dance movement the amazing effect of sounding like a bag pipe. Possibly hinting at the high “voice of one’s own” that shows up in later quartets.

The third movement is inscribed: “Holy hymn of thanksgiving to the deity of a convalescent, in the Lydian key” This is the longest movement in all the quartets. It starts again with the four-notes theme, slightly modified. In the second half of the movement, the theme is modified with one new note and a repeat. A step above the high note is added and returns; Maybe hinting at acceptance.

The fifth movement brings together the sadness/pain with the comforting half step going down. A combination that shows later in 133 and 131.

All the emotional explorations are here, the whole journey is mapped. Yet, the need to “Keep face” and put harmony before truth prevent a complete heart opening as happens in 130 and 131.

Recording links:

Cleveland Quartet (this is only the first movement – but the others are there as well, after search)

130

Here the heart finally fully opens, and the powerful emotions are completely acknowledged and received. I believe that is the reason that the late quartets remain, even after 200 years with relatively few performances and relatively small audience. It is an acquired taste for a painful emotional exploration.

The instruction from the composer for the first and fifth movements include:

“beklemmt.” This can be translated as oppressed, anguished, or stifled.

While the first movement is philosophical and long, exploring the sadness to its roots, it does not find a way out. The way down to the underworld dungeons of depression is a useful exploration. One needs to develop the muscle that can hold on to the apparent meaninglessness, and just trust that there is meaning, even if right now non can be seen.

Although Beethoven uses that same emotional instruction, the ‘oppression’ of the Cavatina is very different. From the first introduction of the theme, one can hear a hint of the deep and complete acceptance that is fully expressed in 135: “must it be? Yes, it must be!”

The sadness of the Cavatina is painfully expressed, at the same time it is vulnerable. It shows human suffering in its raw form, without philosophical covering. Thus, it invites a more human response, mammalian response of care and compassion. Eventually leading towards self-compassion; The ability to accept oneself with all the misery, as a deserving human being who has a gift to share.

The following dance movement is far from pure joy. One might be fooled with the first phrase suggesting it is a simple and jubilant peasants’ dance on a sunny summer day. Yet, the now transformed sadness, fear and anger are now an integral part of joy, making it far more complex.

In the fourth movement, Beethoven demonstrates one move towards integration, by adding structure (variation form) to the pure nostalgia expressed in the opening theme. The beginning of this movement never fails to lead me to tears, not being able to hold the joy and sadness juxtaposition. Can anger, sadness and fear be placed into a structure without losing its energy? Can structure become vital rather than stifling, by integrating one, or several of these raw emotions? It is painful to realize that wallowing in the memories of the past, no matter how good or bad, does not lead to contentment.

Although all the ingredients of the transformation or rather integration of emotions, are clearly there, it will take a few more attempts to get the final resolution of 135

This most beautiful fifth movement is the one of the best attempts at deep acceptance. Deep sadness is moving towards acceptance that can have at times real deep joy in it. The anger is present occasionally, more as life energy that does not lead to fear. The Cavatina is mostly a lullaby, meant to instill the feeling of safety. Nothing to fear, all is well, can open the doors of the heart.

The sixth movement is the last composition Beethoven ever wrote, replacing the original 133. It is far more complex than a simple dance and includes everything learned through the deep exploration of the quartets. For this emotional journey, try listening to 133 after the Cavatina, and keep the sixth movement as a cherry on the cake, after 135.

Recording links:

Hungarian String Quartet (all Beethoven Quartets) 130 starts at 5:30:20

The Great Fugue – 133

The Great Fugue op. 133 was originally composed as the finale of 130. In the first concert, which Beethoven did NOT attend, 130 was received largely well with a few anchors in several movements. However, the fugue was deemed incomprehensible, unpleasant, or repulsive. Beethoven’s friend, the second violinist of the quartet, suggested to him to publish it as a separate piece and write another finale. The publisher supported the idea with a financial incentive, and Beethoven agreed.

Most experts concur that the fugue stands out much better as a separate piece. They also agree that the later composed finale of 130, the very last composition Beethoven wrote, fits better in the composition and architecture of 130. From the view point of the emotional exploration, I am doing here, the finale of 130 which was written after 131 and 135, could also stand on its own, expressing Beethoven readiness to depart with complete acceptance.

The 133 includes and summarizes almost everything I am exploring here.

First, a few quotes:

The 20th century composer Stravinsky: “The Great Fugue … now seems to me the most perfect miracle in music. It is also the most absolutely contemporary piece of music I know, and contemporary forever … Hardly birthmarked by its age, the Great Fugue is, in rhythm alone, more subtle than any music of my own century … I love it beyond everything.”

The great pianist Glenn Gould said: “For me, the ‘Grosse Fuge’ is not only the greatest work Beethoven ever wrote but just about the most astonishing piece in musical literature.”

133 starts with a short introduction where all the motives are presented:

- The architectural theme that is most likely taken from Bach’s B minor fugue in the Well-Tempered Clavier. That theme and its variations goes through all the late quartets. This theme initially holds both the structure and some energy or anger.

- A calming and soothing theme going downwards, possibly derived from the first theme, that feels like a feminine holding. Reminiscent of the Pieta painting and sculptures. The mother holding the pain.

- A trill that can represent joy.

- A big jump up and dotted rhythm energetic theme that seems to protest and shake a fist against God. This theme is a reversal of the “fate” theme from the fifth symphony as explained below.

The actual double fugue that comes after the introduction, uses themes 4 and a variation of 1.

When asked about the fifth symphony famous motive, Beethoven said that it is the sound of fate knocking at the door. Later he is quoted saying that he’ll fight with fate.

Theme 4 uses the notes of the fifth symphony in reverse. In the fifth there are three of the same notes, followed by a fourth lower one (GGGEflat, FFFD). Here in 133 the theme starts by going up into 3 repeats of the same note (DFFF).

Beethoven was reversing fate and standing up to it.

Theme 4 as first presented, is between anger and self-piety. It includes fear and sadness. In the beginning it leads to chaos, developing the fugue to maximum density that is hard to listen to. Towards the end it is mentioned once again, followed by the soothing theme, and both are dismissed.

Instead, theme 4 is played in the higher register softly, calmly, very connected, and ethereally. Echoing the “voice of one’s own” that I mentioned earlier. When 133 was first conceived as the finale of 130, it followed right after the Cavatine where we first heard a full presentation of that voice.

When the anger contains fear, or when fear leads to anger, it can go into terror. The energy is blocked by fear of the stronger power and one can only shake a fist at it with feeling of powerlessness. Here, Beethoven gets to the bottom of the anger, the sadness, and the fear. Breaks each of them to the smallest parts and integrates them together. That turns theme 4 into a “song of myself” that contains contradictions, sadness, joy and fully expressed life energy.

Recording links:

Demystifying Beethoven’s Große Fuge

131

Beethoven considered 131 his best string quartet, maybe his best composition. Everything about it is balanced and complete. In 130 and 133 he worked out all the conflicts and arrived at full acceptance.

The first movement starts with a fugue using another version of the four-notes motive. However, this time the long movement goes as deep as 133 without losing focus or getting into chaos. The pain and sadness are fully there, in harmony with the structure. The “voice of one’s own” also appear early out of the same material.

The second dance movement is also fully coherent, staying focused, joyful yet complex and deep, and not raising doubts or deviating into dark moods.

The third movement is a short recitative. Unlike similar movement, or sections in the previous quartets, it is more declarative, announcing the slow movement.

The long slow movement is an exploration like previous long slow movements. Yet, it is a dance as well. The high register voice, that I associate with soul is no longer alone. It is dancing with all the other voices. The sadness is complete with multi dimensionality of other emotions. The last section is a celebratory procession, but no longer “binding oneself to a joy” so no ground for doubt, but rather a deep confidence and conviction. Notice the unusual sound effects that resemble a tape played backwards. Maybe undoing past mistakes.

The fifth movement brings back a questioning mood, but without breaking the underlying safety.

The sixth movement is a funeral march, coming to terms with death.

Finally, the seventh movement is a complete liberation and a review of all that happened. Almost every idea in previous movement is brought back, all through the lens of free energy, riding on angelic horses.

Recording links:

Jasper String Quartet

135

The choice of F major key, like the Pastorale symphony, conveys a sense that all is well. Safety and harmony.

135 is a relatively short quartet with four movements. After 132, 130 and 131 all around 40 minutes or more, 135 is less than 25 minutes. The previous three quartets have five, six and seven movements. Simplicity is an important aspect of the acceptance and completion reached in his last complete piece. Nothing is complicated. The melodies are simpler and the emotions are held together. The long third movement surely expresses sadness and sorrow, yet there is acceptance in every step and the sadness is never overwhelming. There is an observing part that knows deeply that under all confusion and suffering, all is well.

In the first movement there is simplicity that is convincing, unlike previous attempts.

In the second movement, anger as pure energy is there, it the form holds it safely without diminishing its power.

The third movement explores sadness from this place of deep acceptance. It is simple, and even in moments of questioning there is a clear calming answer. The form is not oppressing but integrating.

The last movement with the inscription “Must it be? Yes, it must be!” regardless if serious or a joke, integrates the raw emotions into a harmonious whole; again, full acceptance.

Recording links:

Ariel Quartet

Was it a joke or serious question?

https://medium.com/@cct_/muss-es-sein-es-muss-sein-and-random-thoughts-1f36d2729fc8

https://slippedisc.com/2020/10/beethoven-is-this-the-end/